We recently heard from a fast-growing, in-the-news company looking to invest in leadership development. This company, like many, is obsessed with talent development, since its ability to be successful and adapt to the marketplace depends on how well its employees learn and adapt. We talked about their needs and various potential approaches.

Then came the (inevitable) question:

“How do you show ROI?”

We get it. Everybody asks this question. Companies want assurance that their time, money and energy are well spent. After the programs are delivered, they want proof of their success–not just feedback or anecdotes, but some kind of hard proof. People might think they have gone through a great program and learned something, but how do you really know?

You will never get in trouble for asking, “What’s the ROI?” Hence, we all pursue the ROI unicorn. If we can manage to find that unicorn, our doubts will go away, our stakeholders will be satisfied, and we will know we have made a contribution. That would be so great!

Hence, leadership development firms come up with models, surveys, and charts that correlate business results with leadership development. Serious-minded panels are held at industry gatherings.

There’s just one problem: it’s all kind of pretend. Searching for ROI when it comes to talent-development programs has very little actual value. And the trouble is, reducing everything to ROI tends to distract us from things that actually matter: namely, how you actually develop the leadership that can help companies and organizations thrive.

To accomplish that, you have to ask a whole different set of questions. This article explains what those questions are.

ROI means return on investment. If you invest a $1,000 in a stock and you sell it at $1,500, you can reasonably claim that your ROI is fifty percent. No controversy there.

ROI works best when used for evaluating investment in capital assets. If you’re producing a particular product, you could invest $1,000 in a new machine. If you have an increase in net income of $2,000, you can assert that you have an ROI of a hundred percent.

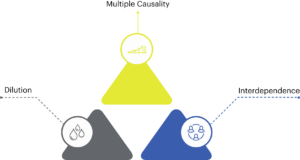

The trouble comes when you move from these simple examples into the real world, where things are highly interdependent. You can make all kinds of correlations between what you invest in and the results you see, but these correlations are likely not proving what you want them to prove. Here are three reasons:

In the real world, you cannot isolate the multiple factors involved in any real-world outcome. For instance, let’s say in the period after the hiring of a new CEO your stock price increases by 20%.

The increase might have been caused by the CEO’s actions. But it could be the result of innumerable other factors: the strength of the economy, changes in regulations, new technologies, the brilliance and dedication of the workforce, etc. Perhaps under a different CEO the stock price would have increased even more. You can’t know.

A particular investment may be successful, but other factors can overshadow and dilute its value. Let’s say you invest in a company-wide diversity and inclusion program and in the year or two following, engagement scores and employee retention are unchanged.

This apparently weak ROI doesn’t actually mean the investment wasn’t worthwhile. You could be undertaking this program during a corporate merger, or in a frothy employment market, or … here’s a crazy thought … amidst a negative and unstable national political situation. Your engagement and retention results might have been far worse without this program.

Adding one new factor usually only creates value if other key inputs are in place. Consider food: salt by itself is not delicious. But salt on French Fries – yum.

Similarly, any investment or support a company provides to an existing workforce is only valuable if there is something valuable to work with. If you develop a new technology, are the wild profits you earn a testament to that technology or to the workforce that applies it?

If you have an awesome leadership program, are the positive outcomes due to the program or to the capabilities and energies of the employees participating in the program?

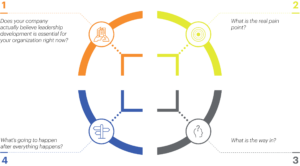

Data are important. But let’s not get wrapped up in chasing ROI. Instead, let’s figure out how to make our work on developing leadership relevant and valuable. This comes down to four key questions.

Your company is either open to leadership development and willing to do something about it, or it isn’t. Most organizations give at least lip service to leadership development, but here are some red flags:

Your company culture favors a fixed mindset over a growth mindset.

In Carol Dweck’s formulation, with a fixed mindset your success is due to innate characteristics, and with a growth mindset success it depends on the efforts you make and your openness to studying your failures as well as your successes.

Fixed-mindset cultures tend to identify people early as “A-players” and “B-players.” They have narrow views of talent. High-potentials tend to look a lot like people who currently occupy the top levels.

Fixed-mindset cultures inevitably constrict the development of leadership, or restrict it to a particular caste of employees.

Your leaders know everything already. If your senior people are always the smartest in the room, and don’t believe they have blind spots, they are unlikely to believe in leadership development programs.

One version of this is, “I never had any leadership training, so I don’t see why others need it.” It almost goes without saying that folks like these are not likely to see any need for themselves to learn or change. Improvement is for other people.

Your stakeholders view their participation as optional. Your company needs to believe that leadership development is critically valuable, and stakeholders need to understand and be involved in the actual work.

Who are all the stakeholders and what do they really want? What value do they see from leadership development? How willing are they to implicate themselves in this process?

If stakeholders don’t believe there’s an urgent need to address your current situation, leadership development will stagnate.

What is the precise problem that you are trying to solve? Leadership is a broad topic. What are the current breakdowns?

Some pain points that we frequently see:

Figure out what the real pain point is and hypothesize what underlying issues might be contributing to it. You don’t need to be exactly correct, but you should have some internal alignment on a focused narrative, not a vague idea of creating “better leaders.”

Do you remember in the original Star Wars movie how Luke Skywalker et al managed to explode the Death Star? He flew his little spacecraft across the vast surface of a groove-filled, planet-sized satellite and then dropped his payload into the one vulnerability in the system. And then, kaboom, and the galaxy returned to peace.

Designing a leadership programs is kind of like this. You probably aren’t going to build leadership by doing everything, or including everyone (at least not at first), and you’re not going to do it through random one-offs.

Further, the presenting issue is often not the real issue. For instance, if your company is currently filled with passion or panic about #MeToo issues, does that mean you will achieve the greatest positive impact by conducting investigations, hiring new compliance people, or having everyone attend a seminar?

Or are there related or deeper needs that would be served through culture building, team alignment, or a leadership needs assessment? For any issue, do you achieve more by starting with senior leaders or with emerging leaders?

It’s not always obvious, but it’s important to figure out what is going to be the best way in. This is one of the ways that we have the most impact with our clients. We can ask the questions that will ensure a focus on the right areas, and we know enough about program design and outcomes to help you avoid investing in work that will not make things better.

For any leadership program there should be a before and an after. “Before” includes clarifying the presenting need and what you are doing to cue things up and foster success. “After” means designing what’s going to happen after the program to ensure sustainable success. You won’t get much value out of the investment if it’s a fleeting success and everybody goes back to their old habits.

Some questions to ask are:

Organizations that get the most out of leadership development and coaching programs pursue value instead of ROI because they know they get more and better that way.

To get an inside view of an organization like this, check out my interview with Pierre Trapanese, CEO of Northland Controls.