Many people start out the new year with some type of resolution—whether it’s to lose weight, get in shape, read more, take more risks, lead more strategically, set clear work/life boundaries—you name it. Some people have initial success, but it’s not uncommon to fall down on these promises to ourselves. And it’s usually not a question of willpower, discipline or even accountability, although these things may certainly help … for a little while at least.

In the book Immunity to Change, authors Bob Keegan and Lisa Lahey examine what stops us from making specific changes, even when we want to make the change. In a study where cardiologists told their patients that they needed to stop smoking and lose weight or they would die, guess how many people actually made the change … one out of seven people! That’s almost 86% who did not make the change, even when faced with death. It begs the question, “What’s really getting in the way?”

If you find that your resolution has gone out the window, chances are that you focused solely on the technical aspect of the change—this is the straight-forward, action-oriented or information-based approach to change. If your New Year’s resolution was to lose 10 pounds, this might look like cutting out carbs and sugar from your diet, working out four times a week, and limiting your overall caloric intake. These are all good things to do to support this goal, and can get you some initial progress, but these are not likely to get you the long-term, sustainable change you are seeking if you are also committed to never feeling deprived.

Keegan & Lahey identified that this kind of competing commitment works as an inner sabotage. It undermines your efforts for change. Like having one foot on the gas and one foot on the brake, you go nowhere, but you also expend a lot of energy. These competing commitments often cause backsliding into old behaviors, rendering most New Year’s resolution-type goals ineffective. This is also why most executive coaching programs are at least six months in duration. There are always quick wins you can achieve, but the return on the investment comes with sustainable behavior change, which can take time to achieve when there are deeply held mindsets, beliefs and assumptions at play.

Competing commitments are sometimes conscious, and sometimes not conscious, or they can straddle the line. Keep in mind, these are not noble intentions, like “I’m committed to living a healthy life.” Competing commitments tend to be things we might be embarrassed to admit to others, such as “I’m committed to never missing out.” However, we all have them—they are based in fear, one of the things we all share in common as human beings. The mere act of articulating these competing commitments can help an individual reach a new level of self-awareness and help pave the way to create change.

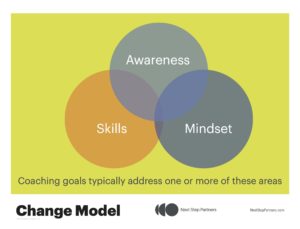

In our executive coaching engagements, to help our clients create the change they are seeking, we typically address one or more of the following areas:

The mindset component plays a key part in the vast majority of our coaching engagements. Each competing commitment is fueled by what Keegan and Lahey call a “Big Assumption.” This is at the heart of the mindset piece, or the adaptive component, of change. It involves examining our underlying beliefs or assumptions about how the world works or the dire consequence that we believe would happen if our fear were to come true (the thing our competing commitment aims to prevent).

In our weight loss example, it might be “If I were to miss out or feel deprived, my life would be boring and unfulfilling.” While this may not seem rational to an outsider, it feels very real to the individual who holds this big assumption. After all, certainty has nothing to do with reality.

Let’s look at a few examples of how addressing the mindset component can help people finally make the change they are seeking.

Goal | Lead More Strategically and Get Out of the Weeds

“Rich” was a coaching client whose development goal was to lead more strategically and get out of the weeds, which would require him to delegate more. Rich would hoard work, causing bottlenecks in getting the work done since he only had so much capacity. Or, when he would delegate, he’d micromanage and stay involved in every detail, instead of focusing on the growth of the business and direction of his team. Through our work, we identified that he had a competing commitment to never being cut out of the loop. As much as he tried to delegate initially, the fear of being cut out of the loop would always pull him back down into the weeds.

We then ask, “What must be true about how he sees the world in order for him to hold on so tightly to this competing commitment?” Rich’s big assumption was that if he were cut out of the loop, he would become irrelevant. Catastrophizing from there is not uncommon. These fears can keep people in an endless loop of behaviors that are counterproductive to the very goals they want to achieve.

This is our “immune system” at work—a system designed to protect us from our deepest fears coming true, and explains perfectly why Rich stays in the weeds. I’ve also seen competing commitments with other clients who have had this same development goal that include “To never being outshined by someone else,” or “To never not getting the credit,” which shows us that the presenting issue or goal may be the same, but the core issue can be different for each person; hence, a one-size-fits-all purely technical approach is not likely to be effective.

Through our coaching work, Rich engaged in several exercises to help him gain distance from his big assumption that being out of the loop would make him irrelevant, allowing him to consciously choose new, different behaviors over time. Among these exercises, Rich conducted regular self-observations in order to notice when his big assumption would pop up and where it would stop him from delegating and focusing on the big picture. We also came up with some safe tests (that didn’t risk re-truing his big assumption), where he could delegate a small portion of a project and see that he was no less relevant than before, and gradually increase the portion he delegated over time. He was able to see that he could still have his team keep him up to date on important details and that he was adding more value by focusing in the bigger, more strategic issues.

Goal | Take More Risks

“Sarah” had the development goal of taking more risks. This was something she wanted her whole team to do, hence, she needed to model this behavior as well—and it was a key growth area for her. Specifically, Sarah’s goal was to make more decisions with less-than-perfect information in the face of uncertainty. We examined all of her behaviors that worked against this goal—things like procrastinating, seeking out more and more information, creating unnecessary complexity to prolong decisions, etc.

Her underlying fear was that she would fail by making the wrong decision, and would then be judged and rejected by others. Here, her competing commitment was “To never fail.” Given this, you can understand why she might get in her own way by putting off decisions. Her big assumption underlying this commitment was “If I were to fail, I would be seen as not smart, and would be marginalized and rejected by others.”

A key part of Sarah’s ability to make progress on her goal was to change the way she perceived failure. To her, failure had been this horrible thing that would damage her career irreparably and cut her off from all future opportunities and people. One of the safe tests we came up with was for her to read a biography of an accomplished business person (e.g., Steve Jobs) to learn about how failure (even a big one like getting fired from the Board) did not need to define an individual’s career or limit future opportunities.

Sarah also spoke with friends and colleagues she respected about the role failure played in their careers. She got a variety of enlightening, constructive perspectives that allowed her to see the potential failure from a wrong decision as far less dire than she had previously seen it. In some cases, she was even able to see how it even led to new opportunities. This had a huge impact on how Sarah perceived taking risks and making decisions in the face of uncertainty. It allowed her to make significant progress in her goal.

We can see from these two examples why change can be hard—even when we really want to make the change. Most of us need help recognizing and unpacking our own competing commitments, big assumptions and other mindsets that get in the way of change. We do this every day through one-on-one Executive Coaching engagements and group Leadership Development programs. Learn more about why we love the Immunity to Change process.