A number of large companies like Adobe, Microsoft, Accenture and GE have decided to eliminate formal performance reviews, relying on managers and leaders to have regular, ongoing feedback conversations with their direct reports.

Regardless of your organization’s approach to performance management, feedback should be given regularly, as opposed to being only a one-time, annual event. This requires that managers and leaders step up and learn how to give effective feedback.

Over the past 15 years, we’ve helped leaders in sectors ranging from professional services, financial services, technology, media and construction to philanthropy and education learn how to give effective feedback.

One of the most common questions we hear is, “How do I deliver improvement feedback that will motivate and inspire better performance, rather than trigger defensiveness—or, god forbid, tears?”

This article shares a simple model that we’ve developed to help deal with defensiveness, should it arise.

One of the biggest impediments to giving improvement feedback is the desire to avoid conflict—or, more specifically, fearing how the other person will react and feeling ill-equipped to handle any defensive or emotional reactions.

Receiving feedback is an emotional process; one that may cause feelings of embarrassment, shame, anger—or possibly pride, elation or relief. In addition, the feedback we give may or may not be consistent with how the other person sees himself and this can trigger some very primal reactions.

The bottom line is that people get defensive because they don’t feel safe.

Our first job as providers of feedback is to create safety in the conversation by establishing a mutual or shared goal for giving the feedback, which we call Shared Intent.

This Shared Intent may be about helping the project run more smoothly, making the other person successful, making the client happy or even building a better working relationship between the giver and receiver of the feedback.

For example:

Action | Start the conversation by establishing your Shared Intent.

The elements of good feedback make for a bigger topic than we can cover here, but keep in mind these general pointers:

Unhelpful

“You need to work on your executive presence and show more gravitas.”

Helpful

Make feedback specific and behaviorally descriptive

“In the Board meeting yesterday, you wavered in your opinion and did not express a firm point of view about which course of action to take….”

Articulate results or impact of the behavior(s)

“…As a result, you did not command the attention of the CEO as much as you could have.”

Make it a two-way dialogue

“What are your thoughts about this?”

Discuss ideas for improvement

“C-level leaders and Board members want to know you have a point of view and are willing to take a stand on important issues. Doing this would help you demonstrate and inspire more confidence.”

Balance improvement feedback over time with praise

While most people struggle with giving improvement feedback, it’s also important to give positive feedback, which can often be overlooked. We, as humans, have a negativity bias, which means that improvement feedback has a stronger and longer impact than praise. It’s important to balance this out over time.

Note—a single feedback conversation may or may not have balanced feedback, and that’s okay. Research suggests that for one piece of improvement feedback, it takes four positive feedback messages to create a perception of balance over time. Further, positive feedback needs to be just as specific as improvement feedback, going beyond the superficial, “Great job!”

Sometimes, despite our best intentions (and improved skill!) in giving feedback, the other person still gets defensive. This can show up in a variety of ways.

“Fight” responses include combativeness, argumentativeness, deflection, blaming, and the like. “Flight” responses may involve the person actually leaving the room or shutting down and getting very quiet. And of course, there is always the potential for tears.

When there are any of these reactions to feedback, the biggest mistake people make is that they continue delivering the feedback, or worse, they start to get equally defensive about the feedback, and keep pushing their message. This will get you nowhere, and can even make the situation worse, creating frustration on both sides.

The key to dealing with defensiveness (or other emotional reactions) is to push the ‘pause’ button on the feedback conversation and deal with the reaction. Think of approaching this part of the conversation in a way that is curious, compassionate and detached.

Download NSP | HEAR™ Feedback Model

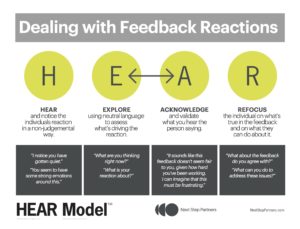

The HEAR™ model is an effective way to deal with defensiveness or other emotional reactions. It involves the following steps:

H | Hear and articulate the reaction in a non-judgmental way.

“I notice you’ve gotten quiet.”

“You seem to have some strong emotions around this.”

E | Explore what is driving the reaction using neutral language

“What are you thinking right now?”

“What’s your reaction about?”

A | Acknowledge and validate what you heard the person say

“It sounds like this feedback doesn’t seem fair to you, given how hard you’ve been working. I can imagine that this must be frustrating.”

R | Refocus the individual on what’s true about the feedback and what they can learn from it and do about it

“What about the feedback do you agree with?”

“What can you do to address these perceptions?”

Note: There might be some iteration between the Explore and Acknowledge steps.

Once you have sufficiently explored the other person’s reaction and acknowledged what is being said (which doesn’t mean you need to agree with it), look for signs that safety has been restored to the conversation. Has the tension or defensiveness been diffused? If so, then you can refocus on the feedback. To further restore safety to the conversation, you may also find it helpful to restate your Shared Intent for giving the feedback.

We encourage you to step into feedback conversations—especially the really tough ones. Feedback requires both thought and preparation. Sometimes, it is the really tough conversations that help us build the relationship, creating mutual trust and understanding. With this trust and understanding, future challenges become much easier to discuss and address.

Don’t let the potential for defensiveness stop you from delivering the feedback. At the end of the day, you can only do your best—you can’t be responsible for other people’s reactions.

Want to learn how to be a pro at delivering effective feedback?. Hear more about the course below.

Contact us if you are an HR manager and would like to audit the course for free.

In addition to our open-enrollment Giving and Receiving Feedback Course, we also offer private courses for organizations that wish to offer leadership development workshops in a closed environment for their employees only. Both in-person and online versions are available. Contact us to learn more.

Rebecca is a Partner at Next Step Partners and is an expert in executive coaching, leadership development and career transition. She has coached individuals throughout the United States and Europe, from high-potential managers to C-level executives. Rebecca has worked with clients that include BNP Paribas, eBay, Google, Genentech, Digital Realty Trust, Clorox, and Nielsen, as well as The Hewlett Foundation, the Stanford Graduate School of Business, and the Wharton School. She has conducted more than a hundred workshops in the United States and abroad on leadership and career development, and is frequently quoted in the press on career issues.

Rebecca graduated as valedictorian from the Leonard N. Stern School of Business at NYU and later received her MBA from Stanford. She then worked as an investment banker for Goldman Sachs in New York and held leadership positions at Disney EMEA in Paris and at Robertson Stephens.